On the state of AI videos

I’ve been working with AI content generation in a startup for over one and a half year at the time of this post. Given the majority form of our content is short video for advisterments, some of our colleague came from creative fields, the following is a back and forth with one of them, Peipei, who worked in film before.

Billy

If we are to look at context as part of the narrative, I want to recognize the mechanics of prompting a video generating model. While on the human side does not seem to involve a lot of creative decision making, when we start to think of the process as a collaborative effort rather than someone hitting a nail with an automatic hammer, it becomes an iterative discourse.

That is, thinking of these models not as tools but inspirations and co-creators. Respect the creative agencies of these “intelligence” systems, noise/randomness or not, treat them as nature phenomenon if you will, harvest the performative nature of them and make something out of it. Computers are thought to be metaphor machines in Wendy Chun’s Programmed Visions, where text are both our familiar vessels for storytelling and the instructional language of computation.

What I am mostly frustrated is the appeal to utilitarian cases for these video models, clips on LinkedIn and twitter making claims to replace existing creatives, hyper-focused on re-creating tired narratives haphazardly stitched together with iconic shots we’ve seen over and over again.

Karri Saarinen from Linear.app recently written a compelling piece about craft, quality, technology and how these things comes in cycles. And in the case of AI generated videos, I see a point of the lacking of craft a symptom of tech industry’s subscription to move fast and break things.

Peipei

I mostly agreed with what Karri Saarinen wrote about in “Why Is Quality So Rare?”, and after reading this article, I found that there’s little I could add to this topic, because it perfectly captures the decline in quality in creation (products in every way, tech, cultural, etc), and about WHY it happened.

Like what he/she mentioned in the article, product creation became metrics-driven. Success metrics became subscriptions/attention, and subscription/attention brings money. I think this “business model” applies not only to streaming platform, who holds the resources, or production houses, who should master their craft and thus provide products with quality, but also content creators, synonym with every-man.

And I think the mindset for most content creators, at least the influential ones, is no different from the studios that make popcorn movies. Don’t get me wrong, I like popcorn movies, the sincere one with characteristics, but in the time when shrinking budgets and poor box office performance have become alarmingly common, they tend to be safe and conservative. What’s worse, I think that in the creation process, creators and audience feed on each other. That is, because the audience’s opinion is too loud to ignore, in order to avoid risk, the creator wants to make a crowd pleaser. However, in the age where people are fed on content specifically tailored for them, taste becomes a drastically individual matter. A crowd pleaser is bound to be meek with no statement.

This is part of the reason why I’m still a skeptic condecerning AI generated video, or the concept of AI as a creator, because AI is built on metrics, data and collective ideas. Even though human seems to have the control button in their hands, the output produced by AI, is a collection of existing, flimsy scraps, built by cutting up crafts and re-forging them in factory. If the output has any characteristics or statement, for now I believe, it would be accidental rather than intentional.

Billy

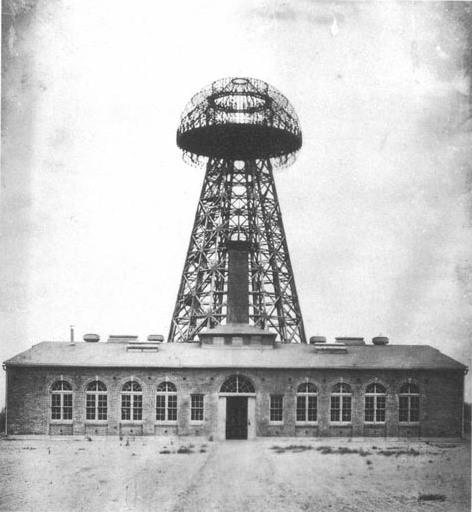

Long Island, 1901, Nikola Tesla started the construction of Wardenclyffe Tower, an experimental facility designed to compete with Guglielmo Marconi’s radio technology. The project was partly financed by J.P. Morgan. After Marconi’s successful transatlantic signal in that same year, Tesla shifted his ambitions to include wireless energy transmission, proposing a global system of free, atmospheric electricity. Morgan, reportedly skeptical of the project’s expanding scope and unclear business model, declined further funding. While never made explicit, it’s widely believed that the absence of a viable path to monetization, particularly the inability to meter and bill for energy, played a role in Morgan’s withdrawal. Without additional backing, construction stalled, and the tower was ultimately dismantled in 1917.

Wardenclyffe wireless station

Wardenclyffe wireless station

We think of technology as tools, and tools as augmentation of the self. Combustion engines packaged with interfaces attached to our limbs allowing us to move across states in a single day. We grew faster and, collectively, stronger. Intellectually, with these booming advancements so rapid that seemed hardly incremental, taking over cultural traditions and rituals that stood for centuries, leaving the collective zeitgeist with a profound sense of unease. In The Weird and the Eerie, Mark Fisher cited the Felixstowe container port, where human workers were replaced by massive robotic cranes, describing a depersonalized lack of agency. This echoes in the data-driven metrics of AI-generated content, it is as if we’ve handed off the steering wheel to some inhuman, ghostly figure, and it’s hard not to bring up capital.

The idea of this exchange of texts came from our shared distaste of the state of AI-generated videos (as of June 2025). A landscape filled with seemingly crowd-pleasing attempts on blockbuster clips, while I can’t help but feel there lies a greater potential for tools like LLMs and video/image generative models. Yet, ultimately, every conversation inevitably resulted in us agreeing but struggling to find a case for that wasted potential. LLMs are inherently powerful creative instruments, and similar to Wardenclyffe Tower, while not taken down, the techno-robber barons of the 21st century have largely channeled these inventions into productivity boosters, market and geopolitical conflict predictors. And that is it, after all the product launches and their magic, we, as creatives, are left feeling bullied by the vastness of this Borgesian corpus mirroring our own image.

Caravaggio, Narcissus, c. 1597–1599

Caravaggio, Narcissus, c. 1597–1599